This is a continuation of a very sensible effort to construct a moral-KFC-Bucket-Thing that is less shit than the morality-proper-KFC that VA has been serving up for a decade or so, and in so doing, perhaps we might also help mister Can to understand the difference between that which is contingent upon something (such as moral norms that derive from evolution or culture) and that which is untethered and entirely random.

In CH1 we established that the proposed morality-proper-WillBouwman-Pete-IWP-Sculptor-ATLA FSK contends that the BDM model of human psychology explains why people in the real world would wish to live according to moral principles at all, and that it is literally sense-less to talk of morality in any terms that place moral motivation in doubt because we must have strayed into talking about some other thing entirely if we are there.

In CH2 we covered the ways in which it is really quite easy to put together a non-teleological explanation for how morality would be constructed from the ground up rather than heaven down. To borrow an analogy from the recently deceased mister Dennett, if the construction can be explained with reference to cranes we have no need to fantasise about skyhooks.

At the end of that second chapter, it became clear that we had probably laid sufficient groundwork for now, and could look at what lies on the next layer up. What goes into making actual judgements, and what informs the content of our moral propositions? I posited then that I would likely make a false-Kantian sort of move in the next part, and it seems I haven't changed my mind, so here goes....

Part 2: The basic rationale...

There's a discontinuity between Kant's two critiques that rarely gets a mention. The pure is a defensive work; it has an ulterior motive to carve the largest possible slice of the universe around us and to keep science out of it. The practical faces no scientific competition, so the move that thwarts science in the former does not really need to be performed in the latter, at least not for Kant's purpose. But that doesn't mean we shouldn't avail ourselves if we are in the mood.

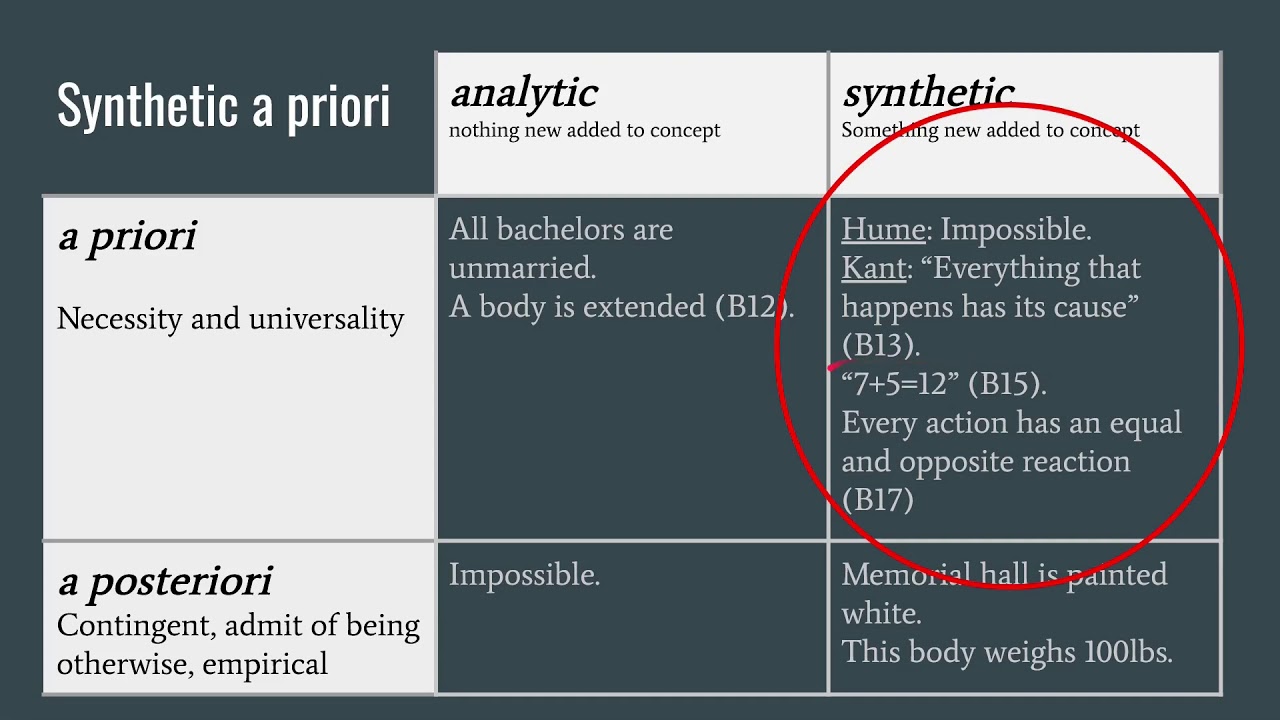

For the uninitiated, Kant draws two lines through the understanding in the Critique of pure reason. One distinction is between the priori and the posteriori. That bit everybody should understand already, a priori is one of the philosophy words that Jacobi uses when he wants to sound educated, if he can do it, so can you. But to underline the matter, a priori truths are known in advance of any experience, while the posteriori follows up behind.

The other relevant distinction lies between the synthetic and the analytic. We may know if an analytic proposition is true by looking at its relation to the concepts expressed ("all bachelors are unmarried men"), whereas for a synthetic proposition we must look for its relation to the world ("All creatures with hearts have kidneys").

Putting aside whatever weird things Kuhn might have got up to, and restricting ourselves to clumsy paradigmatic terms, science can generally be thought of as dealing with synthetic statements and generally posteriori knowings to whatever extent such things are available. Thus, for Kant to pull off his great heist, he needed to move something important into the Synthetic a priori quadrant of this little diagram. <--- youtube video I stole this picture from

Part 3: Kant's categories...

With that move made, Kant was able to assert that we are compelled to view the world around us through certain lenses which are required for any of it to be explicable at all, these are the categories of understanding.

I have no need here to delve into some of the questionable directions Kant took this in, nor to concern myself with Quine or any other carping about the whole notion of a synthetic/analytic distinction.

I do feel that there is a some basic truth that we all can get in the idea that we are not able to participate in the experience of any world around us if we are not already set up to recognise that objects have extension with space, that they have height and width and they weigh something and so on. Does Kant draw a fully distinct line around all and only that which cannot be learned through experience but instead is required to even have experiences here? Probably not, but the general idea works well enough, so I now intend to steal it for my own purposes.

Part 3: Synthetic a priori moral categories of understanding

What we are in search of here is something that undergirds moral perceptions or intuitions, it is far from evident that we could possibly find something by virtue of which moral propositions are true or false. For now that latter can must be kicked once more down the road. We are loking for an equivalent to the notion that one must be primed already to see categories of unity, plurality and totality before one can begin to learn that 3 is more than 2 but less than 7.

Somebody working the other end of the problem, doing a top down skyhooks sort of solution would likely apply their limited scope here. A utilitarian for instance works to exclude the vast majority of our normal moral experience. His main categories being nothing but right and wrong, and the only subcategories being maximised pleasure or minimised. Take any other of the big moral theories and what you are seeing is the same radical pruning operation.

My aim in this post, and all along, has been simply to show that these constrained positions are universally bullshit, that all of the stuff we morally desire must be taken into account because it all reflects what we are required to percieve just to be able to join in this normal part of everyday human life.

One obvious category of moral understanding is equity. The unequal distribution of rights, or favours, or resources is the commonest of scandals. Many non human animals show an awareness of fairness and equity, and so do some children. The problem with equity of course is that another obvious category is desert. When we do not wish to distribute rights or resources equally, we usually say that is because somebody is less deserving than somebody else. So if we are obsessed with diagrams like Kant is, perhaps one quadrant goes to Fairness, with equity and desert as sub categories.

I don't share this formalised diagrams obsession though, so that's probably my only foray into that sort of thing. I don't expect there to be a satisfying neat little bundle of moral categories, the whole thing is really far too messy. But at this point I will open the floor to see if anybody who does like neat bundles has any proposals before I make a mess.